Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (photo from Museum Boerhaave)

Today marks the 100th anniversary of superconductivity by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes. In a superconductor, the electrons flow without any electrical resistance.

Apart from their fundamental scientific interest, superconductors are used to make powerful electromagnets, for example for MRI and NMR machines in medical diagnostics. Other promising applications include power transmission cables with low losses, highly sensitive devices to measure magnetic fields and so on.

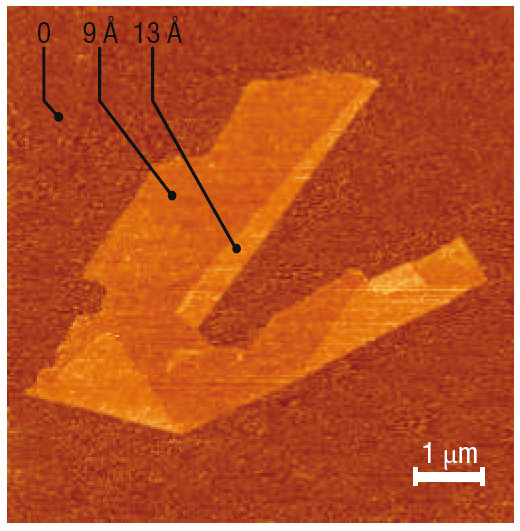

Working in his lab at Leiden University, on 8 April 1911 he experimented with the electrical resistance of mercury at low temperatures. In his notebook he noted that at 3 K (-270°C), ‘Kwik nagenoeg nul’, mercury’s resistance drops to ‘practically zero’.

This discovery at such low temperatures was only made possible by Kamerlingh Onnes previous achievement of liquifying helium at 4.22 K. this provided the means to cool samples down to even lower temperatures. For this breakthrough in cryogenics, Kamerlingh Onnes received the 1913 Nobel prize in physics.

When superconductivity was discovered, it certainly was a puzzling observation at the time. Some scientists believed that at low temperatures electrical resistance would shoot up towards infinity, whereas others thought that it would gradually go down, which is what indeed happens for many materials. However, superconductivity is not simply a new form of electrical resistance – it is a thermodynamic state in its own right, and its unique properties can’t be explained by classical physics alone. Indeed, it was not until 1957, when Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer provided the quantum-theory that explains superconductivity of materials such as mercury.

However, that’s not where research into superconductivity stops. In 1987, the so-called high-temperature superconductors were discovered. Their superconducting temperatures are so high that cooling with helium isn’t even necessary. Interestingly, mercury (Hg) plays a key role there as well: the superconductor with the highest known temperature at normal pressures (135 K) is HgBa2Ca2Cu3Ox!

The origin of superconductivity in these new superconductors is different to the classical superconductors, and remains not fully understood. This makes Kamerlingh Onnes discovery all the more relevant to this day.

Further reading:

it seems this nice article is free access:

van Delft, D., & Kes, P. (2010). The discovery of superconductivity Physics Today, 63 (9) DOI: 10.1063/1.3490499

This post was chosen as an Editor’s Selection for ResearchBlogging.org

This post was chosen as an Editor’s Selection for ResearchBlogging.org

April 8, 2011

1 Comment